FT rules with Presidents Club hit – real world impacts in action

The importance of capturing impacts

The average news consumer skims through dozens of articles a day, hundreds a week, thousands a month and many thousands over the course of a year. The vast majority of these articles leave little or no trace in the memory and indeed have little, if any, impact on the reader’s life, their community or on society at large. But once in a while, a story (usually the result of investigative journalism and resonant with the concerns of the time) is powerful enough to cut through and does generate impacts that are at once individual, societal and political. At AKAS, we call these “Real World Impacts”.

The Financial Times’ investigation into the Presidents Club’s secretive men-only gala that raised millions for charity is one of these impactful stories. Typically, real world impacts can only be judged after a number of months or even years. However, in the case of the FT’s investigation, real world impacts were realised within hours.

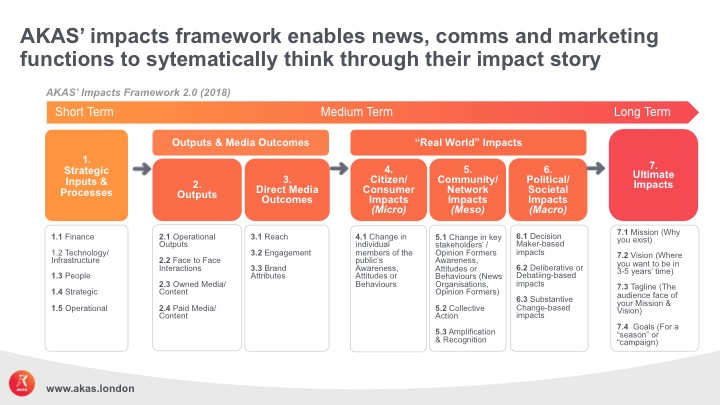

In this article we will use AKAS’ Impacts Framework to explore the wide-ranging real world impacts that this FT story achieved. This framework (see Figure 1 below) enables organisations to think through the impact of their stories systematically. Our clients find this increasingly important in an era of eroded public trust and populist, often vacuous, narratives. Typically, when news, communications and marketing functions think about their impact they focus on their outputs (the content they produce) and their media outcomes (audience reach and engagement, often based on online metrics). They rarely go beyond this to measure the lasting impact of their stories, tracking what happens in the real world at the micro (consumer or citizen) level, the meso (communities and networks) level and the macro (political and societal) level. When they do measure these impacts, they tend to do it in an ad hoc and unstructured way. Yet when news, communications and marketing functions succeed in generating citizen, community and political/societal impacts (through their strategic inputs, outputs and media outcomes), they come closer to achieving their mission, vision and goals: their ultimate desired impact. So when they capture the impact of their stories systematically, they enable a more strategic and evidence-based approach to realising their mission and vision.

The FT is committed to covering the news “without fear and without favour”. Their investigation into the Presidents Club’s men-only charity dinner was an example of just that. Why? Because with this one story, they not only made the audience question sexist structures ingrained within the higher echelons of UK society, but they also provoked a national debate which swiftly led to the closure of the Presidents Club, charities returning donated funds, political resignations and a deepening discussion on the unequal role of women in business and society.

Figure 1:

How the FT’s journalism laid the foundation for real world impacts – understanding the role of inputs, outputs and direct media outcomes.

In terms of strategic inputs (see Figure 1), the FT successfully infiltrated the men-only gala with two (female) reporters appearing as hostesses and recording the event. In terms of outputs, not only did the FT flash the story on its front page for three consecutive days, it also made its undercover video and images available to other news outlets. This multimedia approach made an already compelling news story all the more so. While we do not have access to the FT’s direct audience reach and engagement figures, data from the 2017 Reuters Digital News Report points to the FT’s weekly audience in the UK being relatively small at around 2% of the UK population. Interestingly, however, UK Google searches for “The Financial Times” in the week of the scoop were the highest they had been for 12 months, suggesting that the FT’s direct audience experienced a peak during that week.

In addition, when asked to name the news provider who broke the story, 36% of those who named a provider correctly chose the FT, followed by the BBC (13%) and the Guardian (6%). On the flip side, unfortunately for the FT, this means that 64% of those who named a news provider named the wrong one. Therefore, to fully reap the benefits of breaking this story, the FT needs to use its on-going communications, marketing, campaigning and stories to ensure that a wider audience is aware that they led the investigation.

The “real world” impacts that the FT achieved were enormous.

Citizen and Consumer (micro) impacts are those that lead to changes in an individual’s awareness of an important issue, attitudes towards it or behaviours in relation to it, as a result of a story. AKAS data shows that 41% of the UK public followed the FT story, with 24% following it either very or fairly closely. This represents many multiples of the FT’s direct audience. In terms of awareness, a Populus survey during the week ending 26 January 2018 that asked respondents to spontaneously name the most prominent news stories recorded the Presidents Club story as the third highest (7%), just 1% point behind the Carillion collapse (8%) and Brexit (8%). It’s important to note that in any given week thousands of stories are published. On Twitter, #PresidentsClub was the most used hashtag on the day the story broke. And AKAS’ own flash survey (run on Google Surveys) points to there being some evidence of opinions changing. Following the FT investigation, we asked the public if they agreed with a number of statements even more:

12% agreed more that men-only private clubs should be banned

12% agreed more that male-dominated business culture should end

10% agreed more that event organisers should be better regulated

7% agreed more that more women should be in senior business jobs.

In addition, about 100,000 people signed a petition which was launched on change.org on the day of the FT breaking the story, urging the government to re-introduce section 40 of the 2010 Equality Act, which protected employees from sexual harassment from third parties (like the men at the Presidents Club event) in the workplace.

Nevertheless, it’s too early to say whether these opinion shifts are significant, especially as a Sky Data poll on 26th January showed that 54% thought that men's behaviour at the Presidents Club dinner was typical of men in Britain, while only 33% said it was unusual. In addition, 74% felt men or women-only social events should be allowed to continue, while 17% said they should be banned.

Community and Network (Meso) impacts are impacts that manifest themselves through collective action, amplification or recognition of an important issue. The FT’s story led to a number of immediate community and network impacts. On 24 January, the story was the leading item on BBC News’ main news bulletins, ITV News, Channel 4 News, and Sky News Radio. It continued to resonate on subsequent days, leading to a likely TV reach alone of close to 15 million (c30% of the adult population) for the story. All the leading UK broadsheet newspapers and most of the tabloids led with the story on their front pages on 25th January. Internationally, the story was covered by many leading newspapers online including the New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, El Pais, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, The Times of India and The Australian. It was also covered by broadcasters such as CBS, PBS, Fox News, Bloomberg, Al Jazeera, and France 24.

Within 24 hours of the story breaking, Great Ormond Street Hospital and the Evelina London Children’s Hospital returned their donations from the Club; WPP pulled their sponsorship deal with it; several organisations, which had supported the Club, announced that they were not going to follow through with their donations; a prize of tea with the Governor of the Bank of England was revoked; Tesla and BMW cancelled sales of their luxury cars to the Club; and the 33-year old Presidents Club charity announced it would shut down.

Political or Societal (Macro) impacts are those which cluster around key decision-makers’ actions, significant debates and changes to policy or legislation. The FT story achieved a high number of political and societal macro impacts within 48 hours of the story being published:

- David Meller (a non-executive Director at the Department for Education) who attended the event, resigned, whilst Lord Mendelsohn was effectively sacked from the Labour Party’s front bench for his attendance;

- 41 UK Members of Parliament from all parties were moved to write an open letter to the Charity Commission and to the Presidents Club about the allegations;

- The Prime Minister Theresa May stated on national TV that the event pointed to a deeper structural problem that needed to be addressed in UK society;

- The story kick-started an investigation, headed by Theresa May, into the way non-disclosure agreements are used in sexual harassment cases;

- The Attorney General urged those affected to report what happened to the police as criminal offences were possibly committed;

- The Charity Commission opened an investigation into the Presidents Club;

- Finally, the story amplified significantly the debate over the treatment of women in government, business and society. For example, the Presidents Club event was debated and denounced in the UK Parliament. In the days after the story broke, other media covered examples of harassment in other sectors such as in the hospitality industry and in theatres. The story unlocked a wide-ranging public discourse around the nature of men-only events, and enriched the discourse around the institutionalised objectification of women.

Conclusion – impressive immediate impacts but are they enough to make a sustained difference?

So, we can confidently conclude that this extremely powerful story led to multiple immediate impacts, with probably more to come. It provides another step forward towards redressing gender inequality in the UK. However, one swallow does not a summer make, so many more stories and investigations of this nature are needed in order to sustain the momentum for change. Moreover, systematically recording the real world impacts that each of these stories generate will enable organisations to understand which stories have the highest impact. This, in turn, will help to build the case for future investment in such powerful stories and investigations.

If you would like to follow up on the topics discussed in this article, please contact Luba Kassova or Richard Addy on contact@akas.london